Clinical trials and race

The history of clinical trials shows us why rebuilding trust is important.

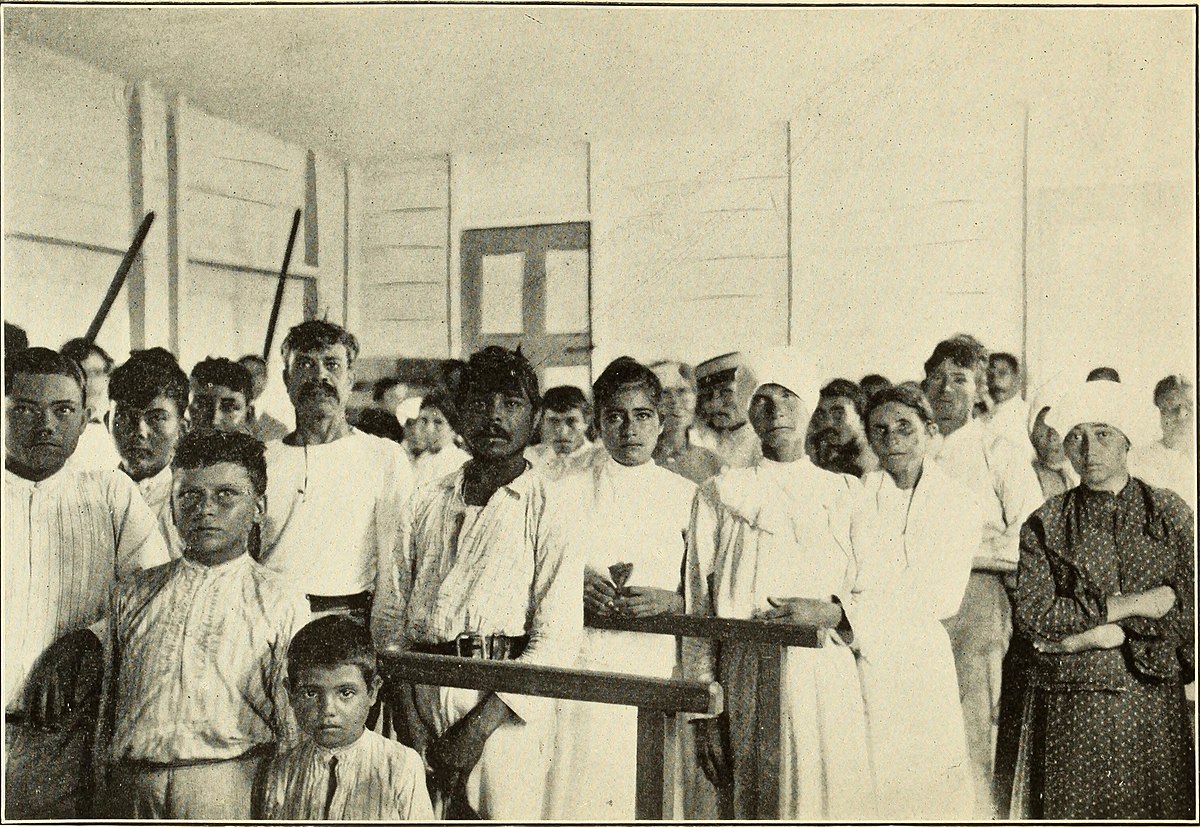

The early origins of medical testing raise important questions about inclusion and fairness—and mistrust. We can’t ignore the impact of many hundreds of years of mistrust on people of color and other groups. We learn from the past as we work to change the future.

History of race and medical mistrust

It’s understandable that some are wary of clinical trials. There is a long and justified history of medical mistrust among people of color in the United States. This mistrust stems from historical injustices that have led individuals and communities to question the intentions of medical research.

A timeline of race and clinical trials

1776

The institution of slavery

1865

Reconstruction era

1907

Early 20th century

These men were victims. They suffered unnecessary harm, as did their families, and many died. This was unethical and immoral and has led to mistrust that lasts to this day. With good reason.

1932 – 1972

Tuskegee study

1951

Henrietta Lacks

1990

Late 20th century

2015

Precision Medicine Initiative

2020

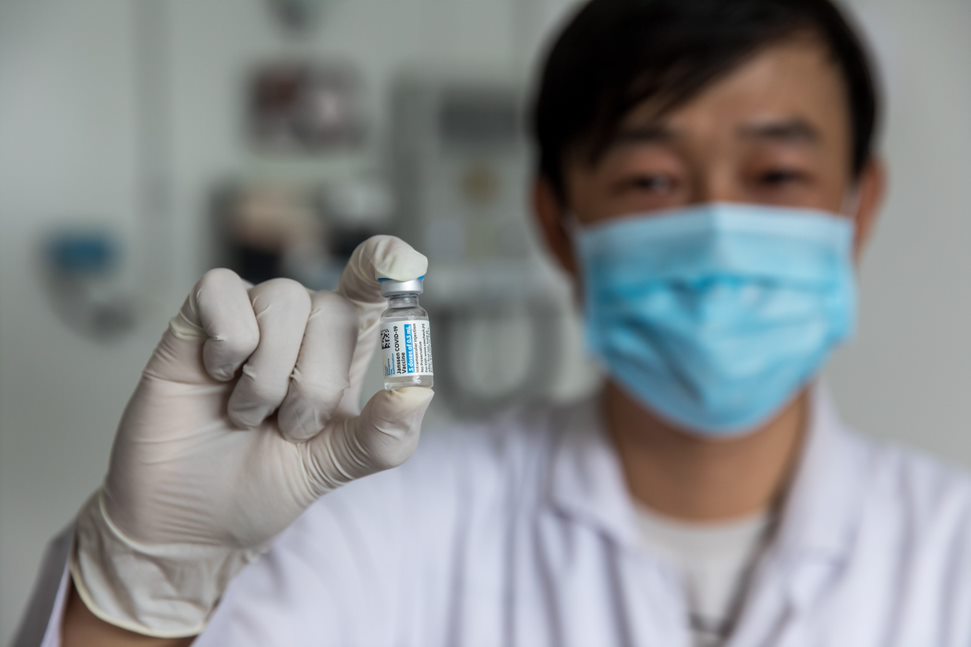

COVID-19 clinical trials

2023

Henrietta Lacks settlement

How past injustices impact today

Today, the effects of this history are still felt. Medical racism, whether it’s obvious or hidden, keeps unfair biases going in the healthcare system. People of color experience inequality in:

- Access to healthcare

- Feeling heard, respected, and taken seriously by healthcare providers

- Quality of healthcare

- Inclusion in clinical trials

- Health outcomes

The legacy of medical racism can be seen today. Bias leads to unequal treatment based on race. Health and disease disparities, gaps in representation in clinical trials, and differences in health outcomes show the widespread impact of medical racism.

Building trust in clinical trials

To build trust, trial sponsors and teams can engage with a wide variety of communities and understand their concerns. They can address social health factors and offer educational resources that help all of us understand trials. We’re headed in the right direction, but there’s a long way to go.

Facts and fiction: a look at misconceptions

When it comes to clinical trials, it’s important to separate fact from fiction. This can help you make a more informed choice about participating. Let’s start by clearing up two misconceptions about clinical trials today.

Placebo

The first time a potential treatment or prevention option is tested in people is in a phase 1 trial. This phase may include small groups of people. And the clinical trials in phase 1 often look to enroll healthy people. Before researchers conduct tests in large groups of people with a specific disease or health condition, they want to learn more about:

- Safety of the potential treatment or prevention

- Potential side effects in people

- Different doses that may be given to people (if applicable)

Trial Teams

Phase 3 clinical trials are a lot like phase 2 clinical trials. Safety tests continue. Side effects are tracked closely. And researchers learn more about how effective a potential treatment or prevention may be. But this phase might enroll an even larger group of people. It may also help researchers compare options. In other words, researchers can find out if a potential treatment or prevention:

- Is more effective than current options

- Has fewer or less severe side effects

- Can be administered less frequently or in a different way

After phase 3, the FDA reviews all results. They decide if the potential treatment or prevention should be approved. This is based on how safe and effective it is when given to people. But the research doesn’t necessarily end there. Phase 4 clinical trials collect more data after approval. This phase typically includes:

- Assessment of long-term safety and effectiveness

- Information collected when the approved treatment or prevention is given to patients under the care of their healthcare providers (rather than the trial medical team)

What else do I need to know?

Clinical trials, sex, and gender

Understand some of the history of clinical trials related to gender and biological sex, and why representation is key.

Your clinical trial experience

If you’re thinking about joining a clinical trial, learn about the typical clinical trial journey for patients.

Find a clinical trial

PAN’s TrialFinder site makes it easy to search for clinical trials based on your condition and location.

Call us for help

Our ComPANion Access Navigators can answer your questions and help you use our trial finder.

1-855-329-5969

Stay connected

We do more than just clinical trial education. Sign up to receive news and updates from the PAN Foundation.